‘Lliahi-a-loʻe

Santalum ellipticum

Mistletoe/Toadflax family (Santalaceae)

Native species ()

Four species of sandalwood, Santalum, are native in Hawaii and formerly produced the Hawaiian sandalwood of commerce. Another has been introduced for forest planting. This species is the most widely distributed through the islands and is an example of the greenish to yellowish flowered sandalwoods. A shrub or small tree to 50 ft (15 ) tall and 1 ft (0.3 ) or more in trunk diameter, with rounded much branched Bark dark gray, rough, deeply furrowed into and rectangular plates, thick. Inner bark red and brown streaked, bitter. Twigs green, hairless, becoming brown.

©2010 Forest And Kim Starr

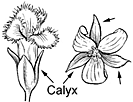

Flower clusters () and lateral, branched, 1–2 inches (2.5–5 ) long. Flowers fragrant, many, short-stalked, about 1⁄4 inch (6 ) long, composed of greenish yellow bell-shaped tube () with four- spreading four short attached at of tube and and with one-celled half inferior, short and 2–4-

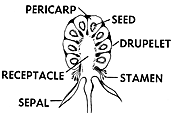

() elliptical of nearly round, about 1⁄2 inch (13 ) long, with ring scar at changing color from green to red and black with blue bloom when mature.

Sandalwood is well known for the fragrance of its heartwood. The Hawaiians called it lā‘au ‘ala (fragrant wood). They made a perfume from the powdered heartwood and added it to their bark cloth. In the Orient, sandalwood served in ornamental carving and cabinet work and as a repellent against insects and was burned for incense. The heartwood is yellow brown, heavy and hard, and very fine-textured. Sapwood is pale brown.

Sandalwood of this and other species is widely scattered through the islands, mostly in dry forests and in lava fields, to about 8000 ft (2438 ) altitude. Santalum ellipticum is best known as a shrub near sea level though it is found up to 2000 ft (610 ), rarely to 7000 ft (2,134 ).

Champion

(Reported as this species but probably S. paniculatum Hook. & Arn.) Height 65 ft (19.8 ), c. b. h. 7.7 ft (2.3 ), spread 48 ft (14.6 ). Honomolino, S. Kona, Hawaii (1968).

Range

Hawaiian Islands only

Sandalwoods differ from most plants in being partial parasites. Their roots become attached to those of nearby plants and obtain some food by robbing these hosts. Thus, establishment of seedlings is uncertain, unless root contact is made with a suitable host.

The history of the sandalwood industry in Hawaii has been told in various references (Degener 1930, p. 142–148). Before Capt. James Cook arrived in Hawaii in 1778, white sandalwood, Santalum album L., from the East Indies supplied the Orient with this valuable, fragrant cabinet wood. In 1791, Capt. John Kendrick, fur trader from Boston, began the sandalwood industry. Price by weight was $125 and up per ton. Export of this important timber brought money, mainly to the chiefs. These leaders were extravagant, purchasing several ships and going into debt. Over many years, they forced the men to labor in the forests, cutting and transporting the wood to harbors on the coasts. Maximum cutting was from about 1810 to 1820. Total sales reached 3 or 4 million dollars. The exports ended before 1845 when the forests became exhausted. There was no planting or forest management. Apparently, the habit may have limited natural regeneration of the wild trees. However, the species of sandalwoods persisted and are not threatened with extinction. Now, they are widespread through the islands, though not in commercial volumes or sizes.

Currently, India is the primary source of sandalwood and sandal oil, which still are important in commerce. Australia also produces some oil. Although much is said of Hawaii’s sandalwood, many other Pacific Islands such as Fiji and the New Hebrides had extensive stands that also were heavily cut during the early 1800s.